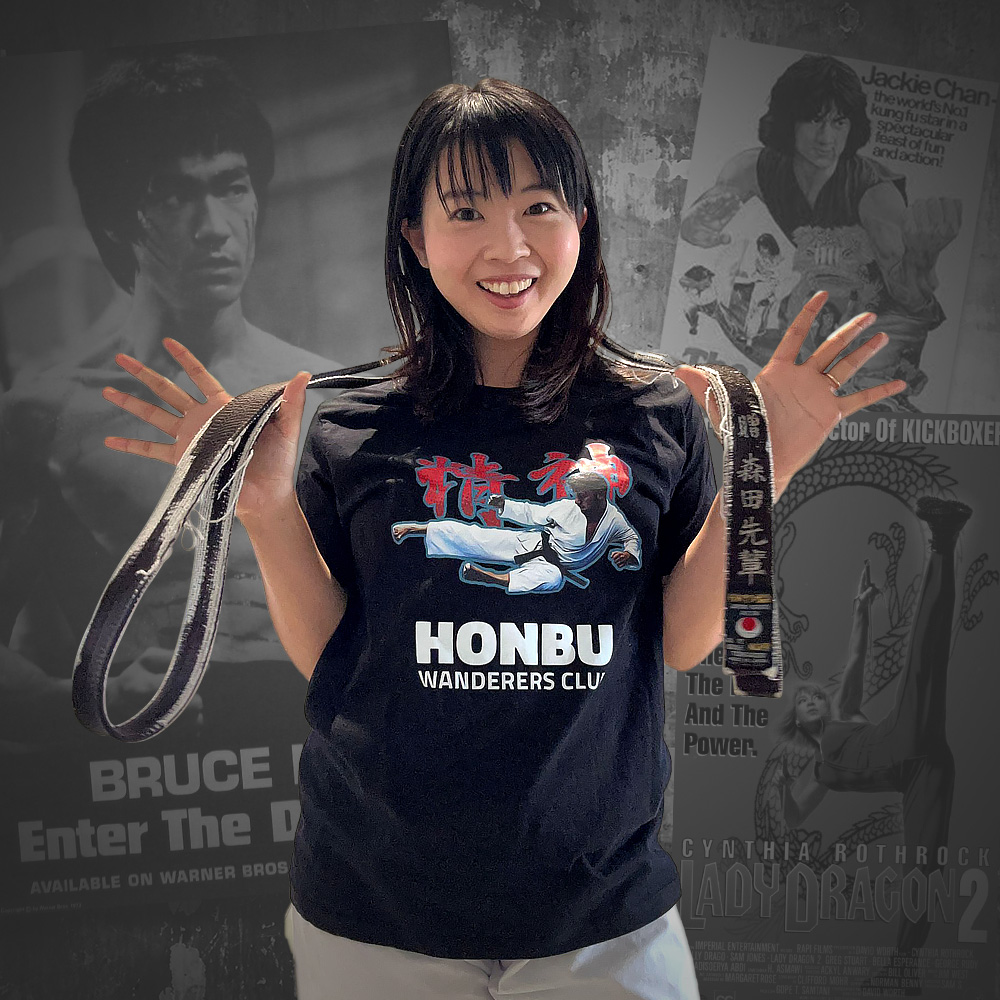

In this exclusive interview with Michiyo Teraoka, we explore the intriguing intersection of her professional journey and her passion for karate.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? Where were you born and raised, and what was your early life like?

I was born and raised in Tokyo, Japan. When I was young, I used to play tag outside every day with my friends.

How were you first introduced to karate? What inspired you to start training in this discipline?

My friends were mostly boys because I was a very active girl. I wanted to be stronger than my friends, so I found a karate dojo near my house, and that’s when I started karate.

Can you share your earliest memories of stepping into a karate dojo for the first time? What were your initial impressions? Were there any mentors or influential figures who guided you in your karate journey? How did they impact your training and mindset?

I embarked on my karate journey at the age of 8. Surprisingly, by the age of 12, I had already achieved the prestigious black belt, although my dedication to karate was somewhat casual at that time, as my primary focus lay on volleyball. I even assumed the role of captain in my junior high school’s volleyball team. However, it wasn’t until high school that I was introduced to the world of JKA karate.

In Japan, extracurricular activities in junior high and high schools carry significant importance, akin to academic pursuits. Every student is required to participate in a club, and these commitments demand a substantial portion of their post-class hours. Upon entering high school, my initial inclination was to join the volleyball club. But my destiny took an unexpected turn. During a club orientation event, where each club showcased their activities, I was captivated by a group of third-year boys executing the synchronized Shotokan kata “Kanku-dai.” In that moment, I developed a deep admiration for their kata, their dedication, their spirit—every facet of it.

From that point onwards, I made the life-altering decision to join the karate club, marking the beginning of my journey into JKA karate. Within the club’s walls, I underwent rigorous training, dedicating 3 hours each day for six days a week. My determination burned brightly as I aspired to earn the approval of the club’s captain, a remarkable karateka in his own right. His stern demeanor and unwavering commitment to discipline within the dojo were renowned. Nevertheless, I cherished every moment of training under his watchful eye, working tirelessly to earn his praise, and achieving the rank of Shodan in 9 months.

Becoming the SA JKA Grand Champion in the ladies division is a remarkable achievement. Can you share the story behind that victory and the emotions you experienced during that competition?

I have a deep love for karate, but more than that, I cherish the people in the JKA family. Training and spending time with them makes me incredibly happy. That’s why I devoted 12 hours a week to training. While it’s true that I had the time for karate because I wasn’t working at that time, I never once felt like I didn’t want to go to the dojo. Training with the JKA family was the happiest time of my life.

When I strive to be faster than the person next to me, when I feel connected through karate regardless of nationality, gender, or age, I experience immense happiness and excitement. I remember visiting the SA JKA Honbu dojo just two days after arriving in Johannesburg because I wanted to make friends there. Looking back, I believe that decision was destiny.

How did your family and friends react to your achievements in karate, both in South Africa and Japan?

My high school sensei was particularly delighted when I resumed my karate journey after stopping when I graduated from high school. Becoming a champion and meeting Sensei Ogura in South Africa, who is my sensei’s sensei, filled him with excitement. My high school’s karate dojo has a long history of around 60 years, with about 1000 graduated students. My sensei even featured my South Africa journey in a magazine for the alumni, which was a great honor.

When I returned to Japan in August, my sensei asked me to share what I had learned in SA JKA. He and my kohais (junior members) were curious about training styles in other countries, and I’m sure they enjoyed it and found new ways to improve their techniques.

Are there any specific moments or events that stand out as pivotal milestones in your karate journey? Did you ever consider competing in other martial arts or sports, or was karate always your primary focus? Can you share some insights into the differences between training in traditional Japanese dojos and the experiences you had training and competing in South Africa?

I am only familiar with the training style of my high school dojo. Comparing my dojo to South African karate, Japanese training tends to be more basic, precise, and slow. In contrast, South African karate training emphasizes fitness, speed, and agility.

For example, when practicing hip and back leg movement in “one-two” (jodan striking toward the jaw and chudan striking toward the solar plexus) with “zenkutsu-dachi” (forward stance), in my dojo, we start by meticulously checking our movements and techniques, then execute 100 punches with 100% effort, taking about 10 minutes for a single technique. In South African karate, we perform only 20 punches for each technique and focus on various other techniques. In my dojo, we believe that our bodies, rather than our brains, should correctly learn the movements, while in South Africa, it involves more mental engagement and a sense of enjoyment and fitness.

Regarding kumite (sparring), in Japan, we engage in free sparring regularly within a team kumite format. It surprised me that SA JKA’s daily training didn’t include as much free sparring.

How do you envision the future of your involvement in karate, and do you have any aspirations or goals you’re still looking to achieve? How did you adapt to the cultural differences between Japan and South Africa? Were there any particular aspects of South African culture that stood out to you?

Adapting to the cultural differences between Japan and South Africa wasn’t challenging for me because I found the two cultures to be surprisingly similar in terms of humility and punctuality. South African senseis sometimes appeared even more humble than Japanese senseis. Moreover, regarding punctuality, I had personal experiences of events not starting on time in South Africa, but under the JKA, everything was consistently on schedule, making me feel like I was back in Japan.

Could you share some insights into the level of competition you encountered in South Africa? Were there any specific training methods or techniques in South African karate that intrigued you or that you found different from what you were used to in Japan?

I believe that South African karate is outstanding. If I had to mention any areas for improvement, it would be to treat certain aspects with more care.

Firstly, equipment maintenance. I’ve observed people discarding their gear after use, which surprised me. In Japan, we are taught that if we cannot respect and take care of our equipment, we cannot reach a high level. It might be related to Shinto beliefs, as we consider items like bags, mitts, belts, and gi to house a form of deity, and we must treat them with respect; otherwise, the spirit of the sport may not favour us.

Secondly, respecting opponents. I noticed a more aggressive approach in South African tournaments, but it’s crucial to control one’s emotions and techniques while showing respect for the opponent.

Lastly, respecting senseis’ words. In Japan, we are taught to listen to our senseis with a “kiwotsuke” attitude, demonstrating our respect for their guidance.

Kiwotsuke is a term deeply rooted in Japanese martial arts culture, particularly in disciplines like karate and judo. It embodies the essential concept of maintaining a respectful and attentive attitude towards one’s instructor or sensei. “Kiwotsuke” signifies a profound level of respect and discipline, emphasizing the importance of listening carefully, following instructions, and showing deference to the teacher’s wisdom and expertise. In practice, it involves adopting a respectful physical posture, maintaining eye contact, and cultivating a humble mindset while receiving guidance. This term underscores the reverence for tradition and hierarchy in Japanese martial arts, fostering a relationship between teacher and student characterized by mutual respect and a commitment to continuous learning and improvement. Martial arts practitioners worldwide often embrace the principles of “kiwotsuke” to cultivate discipline, humility, and effective learning in their martial journey.

Have you adopted new ideas from South African karate in your practice, and do you have any advice for aspiring international competitors?

My advice to aspiring karate practitioners seeking international experiences is to embrace and respect the culture of the country you visit. Learn from different training methods and techniques, and be open to adapting your approach to enrich your own karate journey.

I have indeed incorporated some of the training methods and techniques I learned in South Africa into my practice in Japan, which has enhanced my overall skills.

As for the future, I hope to continue my involvement in JKA karate and serve as a bridge between Japan and South Africa, connecting these two wonderful communities.